Regular Expressions, Lisp, SQL, Parsing, Domain Specific Languages

I’ve been trying to code some more on Project Shelob (my web server) in my spare time. I’m to the point of needing a configuration file, so I can start up the server using different ports and directories for testing.

Speaking of testing, I’m also to the point of needing automated test suites. I was refactoring some of the HTTP code, and when I got done, it was far more readable, and there was much rejoicing! Unfortunately, two days later I discovered I had introduced a subtle bug in keep-alive handling during a 404 event. Oops.

Anyway, I decided to use JSON as my configuration language. Simple, accommodated everything I needed, and later I would be able to easily write an AJAX GUI front end to configure the whole thing. Should be slick, right?

Not as easy as it might sound. Though I have written parsers by hand, I’d rather not. Ok, so I’m using C++, surely someone has written an easy to use open source library that I can just stick in my rules and get out a nice data structure, right?

Well, kind of. There is Boost Spirit which would do everything that I want it to do, but it also required me translating the EBNF grammar of JSON into Boost’s strange amalgamation of YACC and C++. Okay well and good, but surely there is something better?

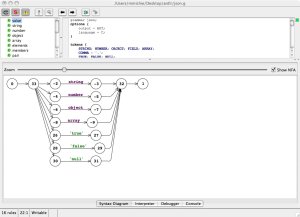

After some more searching, I run across ANTLR which seems to be the spiritual successor to LEX and YACC/Bison. It even has a nice Java GUI and someone had kindly done the ANTLR rules for JSON. Check out the graphical goodness:

Still, the C++ backend wasn’t fully supported and required installing libraries and was complicated. Not 100% what I needed or wanted.

All of which got me thinking about domain specific languages. Most programmers don’t consider it, but SQL and Regular Expressions are good examples of Domain Specific Languages (DSL), as are lex and yacc/bison.

Up till now, I’ve frowned on the whole idea of DSLs in general. It had always seemed like bad software engineering practice to invent a new language for each problem. After all, did we really want to learn an entirely new programming language with each assignment? Who is going to maintain the code?

However, the facts point out that you have to learn an entire API anyway, and the API really just layers over what you’re really trying to do with a language that wasn’t quite expressive enough to do the job natively to begin with.

Which of course leads me to LISP and through Martin Fowler who makes some good points here:

“One of the most obviously DSLy parts of the world is the Unix tradition of writing little languages. These are external DSL systems, that typically use Unix’s built in tools to help with translation. While at university I played a little with lex and yacc - similar tools are a regular part of the Unix tool-chain. These tools make it easy to write parsers and generate code (often in C) for little languages. Awk is a good example of this kind of mini-language.”

While I’ve been using SQL, regular expressions, awk, lex, and yacc for years, I’d never really classified them in my mind as DSLs. I’ve been well aware of the power of small specialized utilities aggregated together to perform a bigger task and why UNIX has been so successful at this, but I hadn’t made the leap to apply this to my programming.

Fowler continues:

“Lisp is probably the strongest example of expressing DSLs directly in the language itself. Symbolic processing is embedded into the name as well as practice of lispers. Doing this is helped by the facilities of lisp - minimalist syntax, closures, and macros present a heady cocktail of DSL tooling. Paul Graham writes a lot about this style of development. Smalltalk also has a strong tradition of this style of development.”

I’ve heard “grey-beards” and academics talk about the power of Lisp for years, and though I did some trivial functional programming in college, I’ve dismissed the rants of the Lisp guys as nothing more than rants. Today though, the ideas are crystallizing in my head, and I’m excited to explore this more.

Comments

Might I recommend you give Ragel a shot?

http://www.cs.queensu.ca/~t...

There is a JSON grammer available for Pike, I'm sure you could steal from it. http://modules.gotpike.org/...

Wow, that looks exactly like what I need. Thanks!

You're what, 30? You're turning into a greybeard!